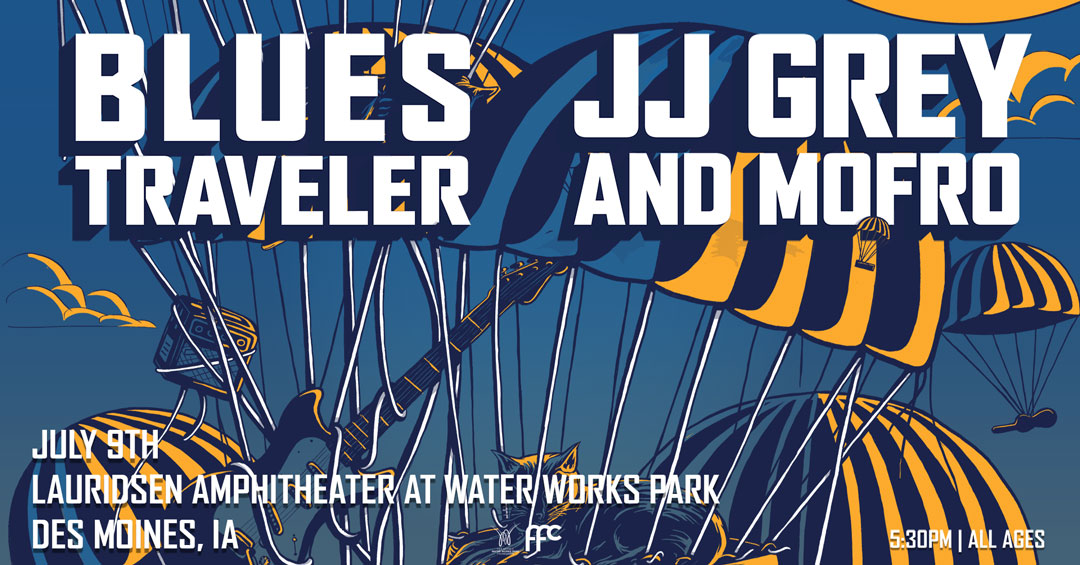

Blues Traveler

30 years ago, the four original members of Blues Traveler, who had known each other since their early teens — John Popper, Chandler Kinchla, the late Bobby Sheehan and Brendan Hill — gathered in the basement of their drummer’s parents’ Princeton, NJ, home and the seeds were planted for a band who has released a total of 13 studio albums, four of which have gone gold, three platinum and one six-times platinum. Over the course of its illustrious career, Blues Traveler has sold more than 10 million combined units worldwide, played over 2,000 live shows in front of more than 30 million people, and, in “Run-Around,” had the longest-charting radio single in Billboard history, which earned them a Grammy® for Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals. Their movie credits include Blues Brothers 2000, Kingpin, Wildflowers and others. A television favorite, they have been featured on Saturday Night Live, Austin City Limits, VH1’s Behind the Music and they hold the record for the most appearances of any artist on The Late Show with David Letterman.

“We started this whole adventure as a team,” says Brendan Hill. “We’ve taken every step of this as a group together, from the basement to moving to New York, getting signed, hiring a manager, to achieving all our goals.”

“I’m a firm believer that rock and roll keeps you young,” adds co-founding member Chan Kinchla. “Because I don’t feel any different than I did when we started, even though I’ve got a wife, two kids and all kind of life in between. We still go back to that mentality we had as kids, smoking pot and learning to jam. We had our first epiphanies about music together. This is a real family affair.”

“The way the songs have held up moves me,” admits legendary frontman Popper, who has gotten down to a svelte 280 from a high of 436 after a gastric bypass 10 years ago, which he admits saved his life. “We’ve really got nothing but love from our audience. If something has quality, it’s constantly reconsidered through the ages. And that’s what we’re doing this for… posterity. We’ve never been 25 before, so having this kind of retrospective, as songwriters, it’s an opportunity for long forgotten songs get their day in court.”

From the suburbs of New Jersey, Blues Traveler moved to New York in the late ’80s, where they became part of a jam-band scene that packed clubs like Nightingale’s, McGoverns and Kenny’s Castaways, where they would share the bill with Spin Doctors and Phish. Represented early on by Bill Graham and son David, Blues Traveler’s live reputation led to a deal with A&M Records, for whom they released their self-titled debut, which produced songs like the hit “But Anyway,” “Gina” and “100 Years,” eventually going gold simultaneously with the album Four. The following year came Travelers & Thieves, also now gold, with songs like “What’s For Breakfast.” The subsequent gold release Save His Soul followed in 1993, with songs like “N.Y. Prophesie,” whose lyrics were actually co-written by John’s Hungarian father, Robert. The recording, and resulting tour, was marked by Popper having to sing from a wheelchair, the result of a motorcycle accident that almost took his life and destroyed the band, which led to a deeper investment from A&M to help support the band during a mettle-testing period in their career.

The band’s Four, released in 1994, was a watershed moment for the group, eventually selling more than six million albums on the strength of the singles “Run-Around” and “Hook.”

“The fact we had that success in the middle of our career, rather than early on, was beneficial because it opened doors to a whole new audience that we continue to court today,” says Hill.

The band’s next album, the now-platinum Straight on till Morning, released in 1997, produced the memorable “Carolina Blues,” a longtime staple of Blues Traveler’s live show. After that, tragedy struck when bassist Bobby Sheehan was found dead in New Orleans on August 20, 1999, at the age of 31. It was a wake-up call for Popper, who vowed to lose his extra weight after help from friends like Howard Stern and Roseanne Barr. Deciding to soldier on, the group brought in Chan’s brother Tad to replace Sheehan on bass and, at the same time, enlisted keyboardist Ben Wilson.

“I kind of vicariously grew up around the band,” says Tad, four years younger than his older brother. “I saw all the trials and tribulations moving forward, and then lightning striking.”

“They wanted to bring in someone who could be part of the band,” recalls Wilson. “They wanted keyboard to play a little bit more of a part of the sound. Apparently, Bobby had always wanted to have a keyboard player in the band. So adding me was a bit of a nod to him.”

The transition took place in 2001 on the aptly named studio album Bridge, the band’s last for major label group Interscope Geffen A&M, on songs like “Back in the Day” and “Girl Inside My Head.”

“That was us looking back,” admits Popper. “It was the end of an era. We wanted to call it ‘Bridge Out of Brooklyn’ as an homage to Bobby, but we decided to talk about where the bridge was going rather than where it was coming from.”

Truth Be Told, recorded in Ojai and Santa Barbara, CA, followed in 2003 on the Sanctuary label and proved a fun experience for the band as they explored their more pop side on songs like Tad’s “Let Her and Let Go” and “Unable to Get Free,” both represented on this compilation.

Bastardos, produced by former Wilco member Jay Bennett for the Vanguard label, featured “Amber Awaits,” Popper’s ode to one of several New England Patriots cheerleaders with whom he fell in love while on a USO Tour of Iraq and Afghanistan. North Hollywood Shootout, recorded in 2008 and released on Verve Forecast, produces a pair of tracks for the collection, Chan Kinchla’s Led Zeppelin-esque “Remember It” and Wilson’s “You, Me and Everything.”

Currently putting the finishing touches on their tenth studio album — the first to feature outside songwriters in addition to the band members’ contributions — the group is taking the opportunity of their milestone to not just look behind, but ahead.

“We intend to keep going as long as they pay us,” laughs Popper, resplendent in bathrobe, Simpsons pajamas and Samurai sword dangling from a belt loop. “We’re going to be in everybody’s face this year. I feel like I’m in my prime. I was convinced I’d be dead at 37.”

“We’re brothers,” concludes Chan. “We’re not done. We’ve got a few more swings left, some more damage to do. I’m sure we bug the shit out of one another at times, but it’s an honor to play onstage with these guys. They are awesome musicians. You have to keep touch with that. And never forget it.”

Still alive and kicking, Blues Traveler prepares for the next 25 years, with a comprehensive overview of the first, in one deluxe package.

JJ Grey & Mofro

From the days of playing greasy local juke joints to headlining major festivals, JJ Grey remains an unfettered, blissful performer, singing with a blue-collared spirit over the bone-deep grooves of his compositions. His presence before an audience is something startling and immediate, at times a funk rave-up, other times a sort of mass-absolution for the mortal weaknesses that make him and his audience human. When you see JJ Grey and his band Mofro live—and you truly, absolutely must—the man is fearless.

Onstage, Grey delivers his songs with compassion and a relentless honesty, but perhaps not until Ol’ Glory has a studio record captured the fierceness and intimacy that defines a Grey live performance. “I wanted that crucial lived-in feel,” Grey says of Ol’ Glory, and here he hits his mark. On the new album, Grey and his current Mofro lineup offer grace and groove in equal measure, with an easygoing quality to the production that makes those beautiful muscular drum-breaks sound as though the band has set up in your living room.

Despite a redoubtable stage presence, Grey does get performance anxiety—specifically, when he’s suspended 50 feet above the soil of his pecan grove, clearing moss from the upper trees.

“The tops of the trees are even worse,” he laughs, “say closer to 70, maybe even 80 feet. I’m not phobic about heights, but I don’t think anyone’s crazy about getting up in a bucket and swinging all around. I wanted to fertilize this year but didn’t get a chance. This February I will, about two tons—to feed the trees.”

When he isn’t touring, Grey exerts his prodigious energies on the family land, a former chicken-farm that was run by his maternal grandmother and grandfather. The farm boasts a recording studio, a warehouse that doubles as Grey’s gym, an open-air barn, and of course those 50-odd pecan trees that occasionally require Grey to go airborne with his sprayer.

For devoted listeners, there is something fitting, even affirmative in Grey’s commitment to the land of his north Florida home. The farms and eddying swamps of his youth are as much a part of Grey’s music as the Louisiana swamp-blues tradition, or the singer’s collection of old Stax records.

As a boy, Grey was drawn to country-rockers, including Jerry Reed, and to Otis Redding and the other luminaries of Memphis soul; Run-D.M.C., meanwhile, played on repeat in the parking lot of his high school (note the hip-hop inflections on “A Night to Remember”). Merging these traditions, and working with a blue-collar ethic that brooked no bullshit, Grey began touring as Mofro in the late ’90s, with backbeats that crossed Steve Cropper with George Clinton and a lyrical directness that made his debut LP Blackwater (2001) a calling-card among roots-rock aficionados. Soon, he was expanding his tours beyond America and the U.K., playing ever-larger clubs and eventually massive festivals, as his fan base grew from a modest group of loyal initiates into something resembling a national coalition.

Grey takes no shortcuts on the homestead, and he certainly takes no shortcuts in his music. While he has metaphorically speaking “drawn blood” making all his albums, his latest effort, Ol’ Glory, found him spending more time than ever working over the new material. A hip-shooting, off-the-cuff performer (often his first vocal takes end up pleasing him best), Grey was able to stretch his legs a bit while constructing the lyrics and vocal lines to Ol’ Glory.

“I would visit it much more often in my mind, visit it more often on the guitar in my house,” Grey says. “I like an album to have a balance, like a novel or like a film. A triumph, a dark brooding moment, or a moment of peace—that’s the only thing I consistently try to achieve with a record.”

Grey has been living this balance throughout his career, and Ol’ Glory is a beautifully paced little film. On “The Island,” Grey sounds like Coleridge on a happy day: “All beneath the canopy / of ageless oaks whose secrets keep / Forever in her beauty / This island is my home.” “A Night to Remember” finds the singer in first-rate swagger: “I flipped up my collar ah man / I went ahead and put on my best James Dean / and you’d a thought I was Clark Gable squinting through that smoke.” And “Turn Loose” has Grey in fast-rhyme mode in keeping with the song’s title: “You work a stride / curbside thumbing a ride / on Lane Avenue / While your kids be on their knees / praying Jesus please.” From the profane to the sacred, the sly to the sublime, Grey feels out his range as a songwriter with ever-greater assurance.

The mood and drive of Ol’ Glory are testament to this achievement. The album ranks with Grey’s very best work; among other things, the secret spirituality of his music is perhaps more accessible here than ever before. On “Everything Is a Song,” he sings of “the joy with no opposite,” a sacred state that Grey describes to me:

“It can happen to anybody: you sit still and you feel things tingling around you, everything’s alive around you, and in that a smile comes on your face involuntarily, and in that I felt no opposite. It has no part of the play of good and bad or of comedy or tragedy. I know it’s just a play on words but it feels like more than just being happy because you got what you wanted — this is a joy. A joy that doesn’t get involved one way or the next; it just is.”

Grey’s most treasured albums include Otis Redding’s In Person at the Whisky a Go Go and Jerry Reed’s greatest hits, and the singer once told me that he grew up “wanting to be Jerry Reed but with less of a country, more of a soul thing.” With Ol’ Glory, Grey does his idols proud. It’s a country record where the stories are all part of one great mystery; it’s a blues record with one foot in the church; it’s a Memphis soul record that takes place in the country.

In short, Ol’ Glory is that most singular thing, a record by JJ Grey—the north Florida sage and soulbent swamp rocker